by Mary Katherine Keown.

by Mary Katherine Keown. SUDBURY, Ont. — Mickey O’Brien enjoys the daily grind of taking a deep dive to the centre of the earth.

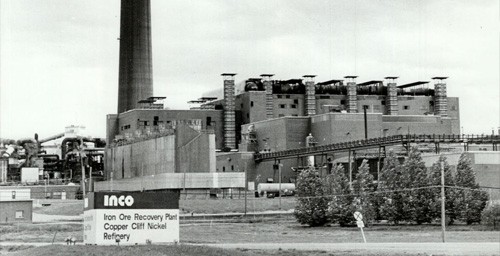

A proud third-generation miner, O’Brien works 10-hour shifts at Vale’s Copper Cliff Mine in Sudbury, Ont. After suiting up and assembling, he and his co-workers break into several crews to begin the hot and dirty task of gnawing away at the earth more than 1.5 kilometres underground.

“I’m on haulage,” O’Brien says. “Right now I’m driving a grader, but I’m being trained on a picker, so if we have big chunks after a blast, the scoop will put them aside and I drill holes in them and I blow them up, and the scoop will come and pick them up. Cool, eh?”

O’Brien is a labour rights activist and considers many of his colleagues — most of whom are members of Steelworkers Local 6500 — to be brothers and sisters.

“I’ve been working on Inco property since I was 18 and I’m 38 now,” he says, referencing the name of his company before it was bought out by Vale in 2006.

The area of underground excavation is expansive. O’Brien says there is a veritable city connecting the former north and south mines.

“I would love to know exactly how many kilometres of drift are driven underneath Copper Cliff,” he says.

While Vale employs about 4,000 people throughout its Ontario operations, more than 13,000 Sudburians work in the mining supply sector; and across Canada, more than 210,000 people work in mining.

The mines in Sudbury are getting increasingly deep. Earlier this year, another company named Glencore announced it was spending nearly $1 billion to mine new ore 2.5 kilometres underground. Vale is also expanding operations at its Copper Cliff Mine with the new multi-million dollar Copper Cliff Deep project.

Drilling deeper

As mines get deeper, Steve Matusch, president of Sudbury-based Ionic Engineering, says they become more expensive and risky for employees. But automation can make them accessible.

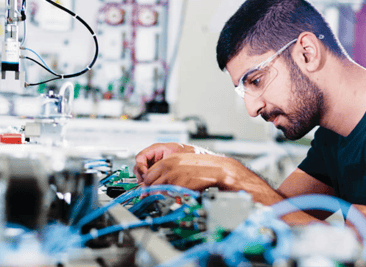

The team at Ionic is working on a number of mining projects aimed at enhancing worker safety.

“A lot of the technology that was not really ready for mining 30 years ago has now become such and so those are the things we’re starting to see — a lot of robotics and vision systems; we’re starting to get into artificial intelligence,” Matusch says.

“A lot of those things are introducing themselves into mining and it is driven by two factors: cost pressures — the ore is getting deeper and more costly to extract; and from a safety perspective, mining is as close on earth as you can come to operating in outer space.

“You’re operating 2.5 miles underground in an environment where you’re totally supported by technology. Without technology, you cannot live in that environment because you need ventilation, lighting, power — all those things that keep people alive. That’s really a foreign situation for people to be in. The drive in the mining industry is to get people out of that situation. That’s going to happen in steps over 30 or 40 years.”

That evolution will allow mining companies to move employees away from situations that can turn dangerous or deadly, and has enabled operations to send fewer people underground, a trend Matusch says will be relentless.

“Without going down this road, you’re facing the choice between some people in the industry or none,” Matusch says. “Without these processes, those deep, deep mines will never be mined. It will be sitting there.”

While historically, mining has been a one-person, one-machine operation, automation is changing the equation and will actually enable employees to work remotely, whether it is around the corner at a cozy café or halfway across the world.

“Traditionally, you would have an operator on the scoop, mucking out the round,” says Don Duval, CEO at NORCAT, a non-profit group that provides health and safety training. “Now, you can actually retrofit the scoop to remove the seat and put on the right infrastructure to enable that scoop to be operated on surface.”

NORCAT runs the only mining research and development centre in the world that operates an underground test facility. As Duval explains, future miners will not only need to be good with their hands, but also need to understand how to use a computer.

“These are different skills than they would have had to have five years ago if they were physically sitting on the vehicle in an underground mining environment,” Duval says excitedly. “That’s the intersection between the future of work and learning, and technology adoption.”

Matusch agrees, although he foresees it happening incrementally. As older people retire, they will be replaced by new employees with new skill sets — including experience with electronics, smart technologies, as well as the care and maintenance of equipment.

Most of the mining workforce is still older than 45 years of age, although the balance is beginning to shift. In 2016, workers aged 45-65 represented 45 per cent of the workforce, a drop from 48 per cent a decade prior. Individuals aged 15-34 years represented 30 per cent of the workforce in 2016, up from 27 per cent 10 years previously.

Matusch says there is a growing demand for employees who work with their hands and minds — electricians, mechanics and trades people, as well as computer programmers and planners. Unskilled positions are slowly disappearing. Since 2006, the sector has increasingly attracted more STEM workers. In 2016, they represented 18.4 per cent of the workforce, up from 17 per cent in 2006.

“If you have a strong technical skill set and you want to work in the mining industry, there’s probably a place for you,” Matusch says.

Despite the fact automation in mining is considered novel and innovative, O’Brien says the technology dates from at least the early 1990s.

O’Brien says these “massive corporations” employ “bean counters” to ensure maximum efficiency; and he points out that at the pinnacle of Inco’s operations in Sudbury, the company employed about 30,000 people. Now Vale has a much smaller staff of fewer than 4,000 hourly workers.

During most of his shifts, O’Brien says there are fewer than 80 people going underground.

“That’s automation and bulk mining; it’s not a new thing,” he says. “One of the greatest things about it is that most of the innovations in mining have come from Sudbury. We have to be proud of our culture and where we’re from.”

If there are fewer people working in the mines, then there are even fewer women who work alongside O’Brien at the Copper Cliff Mine. Currently, women comprise only about 16 per cent, or 33,880 individuals, of the mining workforce in Canada.

While there may be fewer jobs overall, Matusch predicts that automation will make the mining sector increasingly female-friendly.

“There’s no doubt about it, it’s going to be a more diverse workforce,” he says. “Those skill sets that have been associated as traditionally male are going to be the ones that are declining within the mines. The environments are going to be involving a group of people who are very highly skilled, from a diverse set of backgrounds, and that just inherently means more diversity — women, as well as other groups too. It’s going to be a more inclusive environment.”

Recruiting for a new era

NORCAT’s Duval says he has had his eye on automation for a while.

“It’s not just about buying and installing new technologies to achieve desired outcomes, it’s now about making sure we understand the human capital element and the training element to ensure the workers who are operating these pieces of technology know how to do it with confidence and competence,” he says.

Buried deep in the Canadian Shield, about an hour north of Sudbury, Duval says they are testing new technologies, including electric vehicles — an emissions-free underground environment could become a reality — and tele-remote autonomous vehicles.

One of the most interesting things to emerge from NORCAT in the past couple of years is the Ferdeno simulation mine. Launched in 2016, Ferdeno is a training tool that incorporates elements of video games, such as avatars, with the knowledge of decades of underground experience.

“It’s a virtual underground mine, which can be used for a variety of training and development outcomes,” says Duval.

It was initially used to simulate underground mine rescue and has since been used to allow companies to show off their new technologies to prospective customers.

It is also used to recruit a new generation of miners who may not have access to underground facilities. This virtual experience may sway younger people who are still choosing a career path.

“We can put these scenarios in and pieces of equipment in, so a would-be, prospective miner — maybe five years in advance, while they’re still in high school — can really experience Ferdeno, either on a flat screen or with immersive engaged technologies, like augmented reality and virtual reality,” Duval notes.

Ferdeno is just one example of how employers and the industry are responding to new needs and demands from the workforce. As Duval explains, the future of work and learning in the mining industry is “dramatically transforming.”

To make sure they get high-quality recruits, NORCAT tailors learning opportunities to the student. While Duval says there are some components that must be taught the way they have been for decades, nowadays, there are more personalized options available to students, including e-learning and simulation tools, as well as avatar-based learning.

Historically, most training took place in a hands-on, experiential environment with real, live trainers. It was often learn as you go. The point with the new techniques, Duval says, is to ensure students learn what they need to know to work safely and productively.

The workforce will be monitored

At Vale’s Totten Mine in Worthington, about 40 kilometres west of Sudbury, the company has installed a WiFi network underground that includes radio frequency ID tags for all employees. During emergencies, minutes matter and those ID tags save lives.

“In a typical fire underground, if you go to any other plants to clear the mine, it takes about 45 minutes to an hour,” says Derek Kulyski, Totten’s mine manager. “At Totten, we go to the control centre and call up the screen and within five minutes I can tell you who’s in the refuge station and who’s not, and where their last location is. It’s a huge safety piece.”

Totten opened its doors in 2014. In addition to creating a safer environment for its workers, the mine has reduced costs and increased efficiency. Vale hopes it will become an example for other mines.

“We are looking to transform the way we do business, not only at Totten but across our other operations,” said Angie Robson, a Vale spokeswoman. “Our chief operating officer has put it best when he said ‘I imagine a much safer business, where we design our work better, solve problems faster and execute with precision — using technology and data to help us.’”

Robson said work is underway to plan for the adaptation and adoption of technology at other mine sites. She said planning for future projects will include things like an underground WiFi system, as well as autonomous and battery-powered electric vehicles.

At Totten, they are actually running scoops and drills autonomously from the surface. In a video Vale has made available, the company illustrates its operations in Worthington. A man sits in a room, staring at a screen and working two knobs on a table. It is efficient, but more importantly, Kulyski says it helps prevent injury, especially musculoskeletal disorders.

“A scoop operator is highly susceptible to MSD injuries,” Kulyski says. “If we can eliminate a guy jarring around in a scoop for nine hours in a shift, there’s a huge safety component to that.”

O’Brien says automation is inevitable. He points to the fibre optic cables and the ID tags at Copper Cliff Mine, similar to the ones in Worthington, which currently track machines.

“They know how things are moving and this all spills out real-time data to them so they can really analyze their operations to see where the flaws are. It’s actually pretty impressive,” he says. “They have little boxes every so many feet. It’ll read it and say this piece of equipment is between these two points. Eventually they’ll be able to watch everybody and every piece of equipment moving in real time to see exactly what it’s doing.”

Despite the whiff of Big Brother, O’Brien says the increased security of the network is actually a good thing.

“It’s one of the coolest jobs in the world,” he says. “From a safety standpoint, you hit your man-down button, boom — they know right where you are. Can you imagine if you were having a stroke underground? That’s a big deal.”

And while there may be fewer of them these days, O’Brien says the people he works with are like family, and their safety matters.

“Management and staff — we have our beefs,” he says, “but at the end of the day, we spend more time with each other than our real families.”

Still, O’Brien believes these innovative technologies are really about the bottom line and increasing production. For example, by reducing emissions from the vehicles underground, companies can run more equipment and produce more ore.

“It’s probably really all about that,” he says. “There’s a Mark Twain quote: ‘For every hole in the ground, there’s a liar at the top.’”